By Steven Hawley

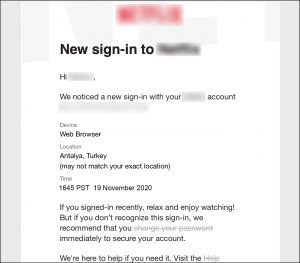

The other day, I received an email from one of the video providers I subscribe to. It seemed innocuous enough.

The phrase “change your password” was clickable, and linked to an online form that was also branded to this video provider. The fields are “User ID,” “Old password” and “New password.” It looked trustworthy. Many consumers think nothing of this, dutifully fill it in, and click “Accept.”

The phrase “change your password” is clickable, and links to an online form that’s branded to this video provider. The fields are “User ID,” “Old password” and “New password.” Many consumers think nothing of this, dutifully fill it in, and click “Accept.”

A few minutes later, you get another email: “Your password has been changed.” And you go on to your next task, thinking no further about it.

Actually, this was not my friendly online video provider at all, but was actually a pirate who purchased a database through clandestine sources (sometimes called “the Dark Web”). Sometimes the pirates are solo actors or a group of friends, but often these pirates are associated with organized crime.

How did this happen?

We’ve all heard of cases where the databases of major financial services companies or consumer brands were breached and millions of consumer records have been stolen. These cases are sometimes publicized by the victimized company or organization as an effort to get out in front of a situation that comprehensive cybersecurity practices would never have allowed to occur in the first place.

Using automation, the pirate that sent this fraudulent email has probably sent thousands of emails just like it to the thousands or millions of users in the database. This automated practice is called credential stuffing: test these data records against the users and collect the hits, which is live personal account information from those who opened the email and clicked through. The sender now has verified access to a large percentage of the original data set.

What happened next?

Some time later, these verified consumers start receiving emails from this seemingly-trustworthy source: “Download our latest software update.” A few days later, strange things started happening. Some of these users started their computers only to be notified that they had to pay $600 to unlock their access (and many do). Other users receive emails telling them that they were detected accessing disreputable Web sites, and to pay $495 to be forgotten. The particularly nasty ones say that they will notify other family members unless you pay up – even if you’ve never visited such sites in your life.

It’s a business model

While much of the publicity about video piracy is about the theft of content or of services, the risk to consumers is real. In our true-to-life example, this “latest software update” was actually a professionally-written malware program that abused the trust of the consumer to execute the pirate’s mission. There’s an active marketplace of malware providers that partner with pirates that use credential stuffing and phishing attacks to deposit such programs onto consumer devices, and when the consumer pays, the pirate and the malware provider split the proceeds.

Consumer self-defense tactics

How can we defend ourselves? Mostly, it’s a matter of common sense. Careful observers may have caught the error in the email message: the time-stamp was in 24-hour notation and the numeral of the date was before the name of the month. If I’m in an American household, this should raise some suspicion because it’s not American date and time notation.

Also, this email didn’t challenge me to prove that I was me. If the Web sites that you do business with offer two-factor authentication, enable it – yes it’s annoying but the alternatives are more so.

Another one of those emails says “Your password has been changed.” Except that I have not changed my password. For many, the impulse would have been to click through and find out more. But being sufficiently paranoid, I have learned to know better.

Also, rather than clicking through the link in an email, especially if it’s a link to access a consumer account that’s linked to a payment account; it’s always best to access the service’s Web site directly. Make sure the little lock appears next to the URL in your browser. In fact, set your browser to notify you if you happen upon a suspicious Web site. If you operate a Web site, make sure you set it up with SSL (https).

How service providers can help

By and large, consumers are unaware that most Internet service providers – whether it’s a Cable TV operator, a Telco, or in my case, the company that hosts my Internet domain and Web site – have tools that enable consumers to identify fraudulent email messages. In my case, it’s an “email validation service” that allows me to paste the header and contents of the email into a field, click “Submit” and receive instant verification as to whether or not the email is authentic.

Does the average consumer know to do this? Does the user know what an email header is or where to look? Or, as a service provider, maybe the better question to ask is “How can we take a role in making the consumer aware of such things, and make it easy for them to do.”