An extensively researched technical report containing the first empirical data about the performance of Italy’s legally-mandated Piracy Shield platform recognized serious errors and recommended prompt action.

First, some historical context. In recognition of huge and increasing financial losses by sports leagues over the years, Italy passed a law in 2023 that required ISPs to block IP addresses and Fully Qualified Domain Names (FQDNs) when notified of infringing football distribution by rights-holders.

Controversially, blocking must occur within 30 minutes of notification – giving ISPs little opportunity to prove infringement themselves. In support of such rapid blocking, Italy implemented Piracy Shield, an automated piracy incident reporting and ticketing platform that manages the notifications to ISPs. Italy’s telecom and media regulator, AGCOM, is responsible for its operation.

The law was modified in October 2024, so IPs and FQDNs can be blocked if they are used predominantly (not necessarily exclusively) for illegal activities – without defining what “predominantly” means in practice. The report’s authors believe that only Google is following this mandate.

The 30-minute blocking requirement was extended to VPN and DNS providers in 2024, and further extended beyond football in 2025, to include live movies and TV series programming.

Errors and protests emerge

Over the course of 2024, there were many reports that Piracy Shield was calling for site blocking against legitimate commercial Web sites, which had an impact on those businesses. AGCOM’s President defended its activities and positioned Piracy Shield as a work in progress that was undergoing continuing improvement through fine-tuning.

In October 2024, a copyright holder submitted a blocking request for a subdomain of the CDN of Google that supports the functioning of Google Drive and Youtube. As consequence, those two services were blocked in Italy for several hours. The block was lifted several hours later but due to DNS caching, the effects of the block persisted throughout the next day.

In November 2024, one of AGCOM’s own commissioners, Elisa Giomi, could no longer maintain her silence, and issued two lengthy statements on LinkedIn. Her first statement was to distance herself from the defensive position taken by the President. The subsequent statement added that AGCOM “risks unintentionally limiting freedom of expression” and engages in censorship.

Effectiveness called into question

Although AGCOM enforces blocking orders via Piracy Shield, the list of affected IP addresses and domain names is not publicly disclosed. The report contends that this situation may stem from operational considerations (e.g., to avoid circumvention by infringers), lack of a legal mandate to publish, and a regulatory balance that favors enforcement efficiency over full transparency.

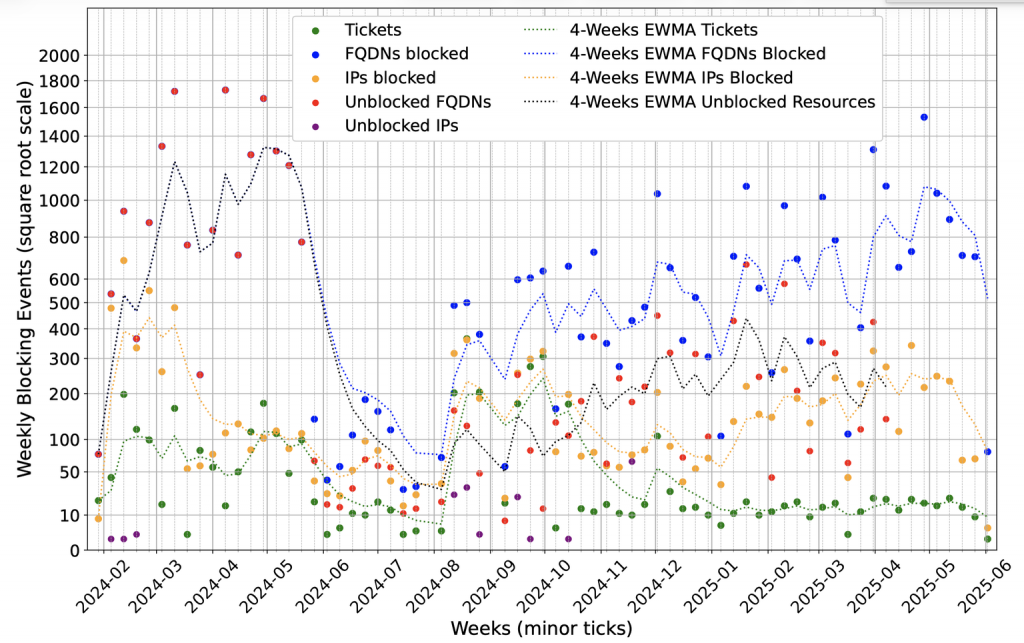

By reconstructing and analyzing the set of blocked resources from a leaked GitHub public source, the report illustrates Piracy Shield’s operation and the extent of the collateral damage it causes to legitimate Internet services.

Errors continue

In June 2025, researchers found that Piracy Shield was blocking 10,918 IPv4 addresses and 18,849 domains, and found that more than 500 confirmed websites unrelated to streaming were blocked, and over time the number of affected sites went into the thousands.

Most of the damage came from IP-level blocking. In shared hosting, or when providers reassigned an IP after abuse, a single blocked address could take down dozens of unrelated domains. In some cases, one IP block was enough to silence entire groups of legitimate services.

Another error is one of omission. Researchers found that Piracy Shield’s blocking mechanism targets only IPv4 and FQDNs, with no evidence of filtering on IPv6, despite IPv6 being fully supported. This creates a potential loophole, allowing illegal streaming operators to use IPv6 to bypass the platform.

They found that 132 FQDNs (2.0%) already resolved to IPv6 on the date that they were blocked, while 1,568 (23.6%) started doing so afterward. This post-block increase suggests a possibility that some operators may be using it to evade blocking.

Conclusions and recommendations

The report questions Piracy Shield’s effectiveness in curbing illegal streams, as evidence suggests that operators may evade blocking. The report’s data shows hundreds of legitimate websites blocked, leased address space rendered unusable, and risks emerging even for national infrastructure.

In light of these findings, we urge authorities to reconsider the platform’s core principles and to explore more viable, transparent approaches to combating illegal streaming

About the report

The September report was published by RIPE NCC (Réseaux IP Européens Network Coordination Centre), a regional Internet registrar with over 20,000 Local Internet Registries (LIRs) that provide Internet services across 76 countries for Europe, Middle East and Central Asia.

Why it matters

This analysis shows that the Piracy Shield platform indiscriminate IP-level blocking, and continues to disrupt hundreds of legitimate, non-streaming websites. At the same time, the platform’s effectiveness may have been undermined by streamers who evaded enforcement by migrating to new infrastructure and unfiltered IP address space.

Based on these findings, the report calls upon policymakers to critically reconsider the core principles in this blocking approach. The evidence suggests that its broad impact on legitimate services and the potential national security risks outweigh the intended benefits.

Further reading

Live event blocking at scale: Effectiveness vs collateral damage in Italy’s Piracy Shield. Summary article. September 2025. RIPE Labs.

90th Minute: A first look to collateral damages and efficacy of Italian Piracy Shield. Full report (PDF), to be published in IEEE Xplore. September, 2025. by Raffaele Sommese, Anna Sperotto, Antonio Prado, Jeroen van der Ham, Antonia Affinito (University of Twente, The Netherlands), (Unidentified) Independent Consultant, Italy. This version was published online via University of Twente.